QC Story – The Diagnostic Process

by: Quest Claire

I like to continue discussing an important phase of the QC Story Procedure with the concerned parties for some of our vendors. This important phase, the diagnostic process, is considered to be the core of the Pareto Principle and the problem-solving process.

The first step of this diagnostic process is to understand the symptoms correctly. If this understanding is derived solely from regular field and shop reports, the nominated person or assigned team can be misled through undiscovered confusion and vagueness.

In terms of clear concepts, the team members should develop an awareness of the distinctions among essential concepts such as defect, symptom, theory, cause, remedy, etc., as outlined in the previous article “Define the Problem”.

The meanings of Words Used to describe symptoms should be defined and consistently used. It is very common for these words to have multiple meanings. Some descriptive words, e.g., “oversize,” may cover several degrees of seriousness. In such cases, it is helpful in the diagnosis of symptoms to use several terms to describe these degrees, e.g., “Oversize (critical),” “Oversize (major),” and “Oversize (minor).” Other descriptive words are generic in nature, e.g., “malfunction.” Such a word may describe several very different symptoms (e.g., open circuit, reversed wiring, dead battery), which trail back to very different causes.

A widespread source of confusion is variation in departmental dialect. For example, to the accountant, “scrap” may mean anything thrown away, no matter what the reason; to the quality specialist, “scrap” is something thrown away because of nonconformance or unfitness for use.

This lack of standardization in the meanings of words can confuse managers regarding the effect of defects. For example, in a toy manufacturing company, the term “aesthetic defect was the company dialect for surface marks (scratches on the outer surface of a doll or molding defect from plastic injection). This term failed to distinguish many different aspects of fitness for use:

1. Damage in the outer surface, which significantly impairs fitness for use

2. Damage that does not significantly impair fitness for use as it is located on a secondary surface of less importance but which may be visible to the user during normal use

3. Damage that does not impair fitness for use at all as it is located on the surface of an internal part and which is not visible to the user during normal use

The lack of standardization can also confuse managers regarding the causes of defects. In a plant making rubber products, there were several sources of torn products: the stripping operation, the machine cutting operation, and the assembly operation. The single word “tears” failed to distinguish among strip tears, click tears and assembly tears. One of these categories was largely operator-controllable but involved only 15% of all tears. However, a manager may have assumed all the defects to be operator controllable.

Autopsy of Product:

This could be an essential device for cutting through the confusion in terminology. It means literally to see with one’s own eyes. The nominated team, and of course, the members who conduct the diagnostics, should get their hands on the product and learn first-hand how the words used relate to the observed conditions of the product. This seeing with one’s own eyes is of added value in stimulating realistic theories of causation.

Quantification:

The frequency and intensity of symptoms are significant in pointing to directions for analysis. The Pareto principle, applied to past performance records, can significantly aid in quantifying the symptom pattern. For example, a toy company undertook a project to reduce quality losses in the spray-painting department. The previous article, “The Pareto Principle,” showed the Pareto study of the defects within the department based on production data from four consecutive weeks. The intensity of the problem reflected that the first three painting operators account for 73.8% of all rejections. This information is an obvious aid to the nominated team in setting their study priorities.

Formulation and Confirmation of Theories:

As symptoms of defects are studied, the question is raised ”What causes defect X?” The responses are mainly assertions or theories. The diagnostic process includes a test of these theories, disproving some assertions and affirming the possibilities of others until there is established a cause-and-effect relationship which then leads to the remedy process. The need for a supply of theories is obvious.

Formulation of Theories:

There are several sources of theories of what causes defects, including:

1. The manufacturing management: These men have long been associated with chronic problems. They have given it much thought, harbor some apparent theories, and have done inconclusive experimenting. When some one writes on the blackboard, “What causes defect X?” the team members have many theories to offer. However, the causes that finally became genuinely dominant were mostly on the list of theories initially claimed by the manufacturing management.

2. The diagnosticians: Once they come to grips with the data, they identify possible relationships and advance theories. Usually, that serves to unify theories advanced by the manufacturing management, but sometimes there are brand new ones.

3. The workforce. The workforce evolves its theories through intimate association with material, process, and product details. Whether these theories are contributive depends largely on the relationship climate between the managers and the production operators. This climate may inhibit the managers from asking and the workforce from responding.

Theories may be secured from the workforce in several ways:

1. by a direct request: A factory making mechanical springs experienced field usage trouble due to some springs being too weak. The foreman answered that he had observed that during the counting of springs (by weight), the weigher would pull springs out of the entangled supply box to complete the count. The foreman believed that this pulling weakened some springs caught in the entanglement. He was the sole source of this theory, which identified the sole dominant cause.

2. by a standing suggestion system: The regular suggestion systems always turn up some ideas relating to quality. The Process Improvement Program becomes one of the motivational programs that result in an effective suggestion system directed specifically to quality matters.

3. from defenses set up by the workforce: Operators who are criticized for making errors often defend themselves by assertions that the defects are caused in other ways.

4. from involuntary theories: Whenever it is observed that some operators consistently turn out work superior to others, a shop study may disclose the cause of this difference as a form of secret knowledge, which is unknown to the production manufacturing management.

Theories of Defective Systems: Theories of causation should not be limited to products and processes; they should also extend to broader systems. At a meeting of managers, one man reported the observation: That’s the third time this month we lost many products due to instruments out of calibration. It is a shrewd observation since the three lots consisted of different products. The system for maintaining the devices in calibration is now placed under suspicion. He was always thinking outside the box, being creative, and never trotting on the same old path often, allowing real causes of a problem to surface. Otherwise, such causes remain hidden for a much longer time.

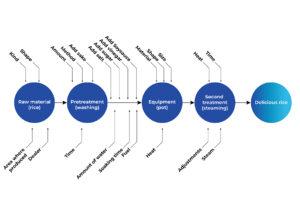

Upon completion of the diagnostic process, a cause-and-effect diagram could be written down showing all elements seemingly related to the problem while removing all that is irrelevant. The following represents a simple Rice Cooking cause-and-effect diagram for reference.

Preliminary Diagram:

A detailed cause-and-effect diagram could then be developed, showing all elements seemingly related to the problem. It is important to know that these elements must include those pertaining to sporadic and chronic problems, which require different methods and processes to restore control of the process or remove the sporadic problems. As far as dealing with chronic problems is concerned, pulling in company-wide breakthrough efforts is often required.

Therefore, identifying the vital few defects as the first milestone and using the Pareto principle, as discussed in The QC Story Procedure, is worth attention in the diagnostic process.

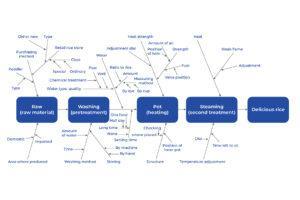

The following is a comprehensive representation of a simple Rice Cooking cause-and-effect diagram.

Comprehensive Diagram:

I want to cover the remedial process in the forthcoming articles.