QC Story – Define the Problem

by: Quest Claire

As covered in the article “The QC Story Procedure,” published previously, I stated that any recommended process improvement actions must be clearly understood, backed by reasons, and supported by evidence. I, therefore, need to present the QC Story Procedure to the concerned parties for some of our vendors. I also need to emphasize that any process improvement plan must be directed toward a clear identification of the problem, in terms of the nature of the problem – sporadic or chronic, the frequency of the problem, and the designation of responsibilities for solving the problem, to secure the confidence of their company management. The magnitude of the process problem is also presented in terms of performance loss and the corresponding projected overall cost reduction to be achieved once the process improvement actions are completed and maintained.

I want to start our discussion of the QC Story Procedure by defining some critical terms and clarifying some essential concepts as follows:

A defect is any state of unfitness for use, or nonconformance to specification, e.g., feature malfunction, oversize, undersize, poor appearance, etc.

A problem is the undesirable result of a job resulting from defects. The defects may be so minor that nothing needs to be done. At the other extreme, the defects may constitute a significant problem that an organized approach must be structured for a solution.

A project is a problem selected for a solution through an organized investigation, diagnosis, and corrective action approach.

A symptom is an observable phenomenon arising from and accompanying a defect. It may be used both as a defect and symptom description.

A theory is an unproved assertion as to reasons for the existence of defects and symptoms. Practically, multiple theories are proposed to explain the presence of the observed phenomena.

A cause is a proven reason for the existence of the defect. Sometimes there are multiple causes, in which case they follow the Pareto principle, i.e., the vital few causes dominate all the rest.

A dominant cause is a major contributor to the existence of defects that must be remedied before an adequate solution exists.

Diagnosis is the process of studying symptoms, taking and analyzing data, conducting experiments to test theories, and establishing relationships between causes and effects.

A remedy (corrective action) is a change which can successfully eliminate or neutralize the cause of the defect. Usually, there are multiple proposals for remedy, and the remedial process must be chosen from the alternatives. In an extreme situation, a remedy occurs without sufficient knowledge of the causes, e.g., replacing a defective unit with a new one for a customer.

The solution to a problem is to improve the poor result to a reasonable and satisfactory level.

My previous article defined The Problem as “A problem is the undesirable result of a job.” Since this is a broad definition, I need to elaborate further to confine its meaning to the scope of the QC Story Procedure. In my many years of QC/QA experience, I understand its importance that certain conditions must be met to apply the QC Story Procedure and get the corresponding benefits. When such conditions are met, a problem is then well-defined. A clear identification and definition of the problem to be dealt with for a project is the key to success.

A good problem statement has the following characteristics:-

Observable: The problem must be seen and evidenced by its symptoms. Symptoms are outward evidence that the problem exists.

Specific: The problem statement should focus on specific products, services, or information, a specific part of the organization, or a specific part of a large problem.

Measurable: The problem must be stated in terms that can be measured by using an existing measurement system or creating a new one. Although the problem may have yet to be measured to date, problem-solving teams must be able to conceptualize how it could be measured in quantifiable terms.

Manageable: The problem statement must be narrow enough in scope that the teams can solve it within a reasonable application of resources over a reasonable period. Gigantic projects should be avoided.

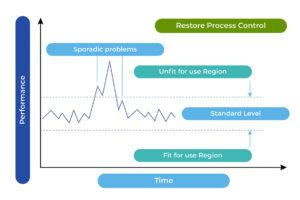

I also understand that The QC Story Procedure is designed to resolve sporadic problems and restore process control but is not intended to address chronic problems, which usually require more company-wide breakthrough improvement actions. Chronic problems, therefore, fall beyond the scope of the QC Story Procedure. I want to outline the difference between these two types of problems as follows:

Sporadic problems

All continuing performances are subject to variation. Some of these variations are nonsignificant and are ignored or deferred as to corrective actions. Other variations are so significant that they trigger the alarm signals of the control system. These significant variations are categorized as a form of sporadic departure from standards and demand that the personnel responsible for process control takes notice of the alarm signals and takes steps to restore the status quo by

(1) discovering which process changes created the symptoms accountable for the alarm signals, and

(2) removing the causes of the changes.

The following figure shows a typical performance history embodying a sporadic departure from the standards. The sequence of events used to restore the status quo can be called variously as troubleshooting, firefighting, etc., in principle by removing the assignable causes of the sporadic problems. It constitutes an essential human activity and happens often enough to suggest that those responsible for meeting the standards should be trained in the required troubleshooting technique.

Chronic problems

In any system of control, the standard level of performance is also the goal. Implicit in this concept is the assumption that it is not economical (or even possible with known technology) to improve on the standard level.

Nevertheless, managers know that what used to be standard levels have often been made obsolete through improvements achieved by determination. The process of achieving such improvements differs remarkably from the control process since, at the very outset, the standard level is regarded as inferior performance. The difference between the (old) standard level and a proposed (new) level is regarded as a “chronic problem,” for which a remedy can only be found by determination, in principle, by removing many of those unassignable causes of the chronic causes of the problems. When a new, superior level of performance is attained as the result of such human determination, it is called a” breakthrough.”

The following figure shows the breakthrough concept of improving standard performance graphically.

Some breakthrough phenomena differ from those depicted in the above figure chart. In many processes, reduction in process variation to a degree never previously attained can constitute a much more desirable breakthrough.

Continue to read the next article The QC Story Procedure: The Pareto Principle